The History of Indian

The History of Indian is living & continuing daily, and has been changing since 1901, the saga of how it has un-ravelled since that time has been colourful with many ups & downs with changes of economy,mismanagement, & wars, still this continues to play-out with today a new company tracing it’s roots back to George Hendee. The film The World’s Fastest Indian when released was very successful at the box office, the History of Indian if on film would be regarded a fictional, but in truth “Fact is Stranger than Fiction”, it would be riveting viewing.

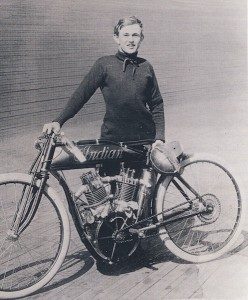

No doubt about it, the 1911 Senior TT race, held for the first time over the Isle of Man’s Snaefell mountain circuit, gave the home motor cycle industry a salutary lesson. To that point, the average British machine was belt-driven and single-geared – or, if it had gearing at all, this would be by an epicyclic rear hub of remarkable frailty. Yet here were three foreign models, Indian vee-twins from the USA, romping home in first, second and third places, and the fact that they were ridden by Britons (Oliver Godfrey, Charles B. Franklin, and Arthur Moorhouse) did little to salve the wound. The Indians employed chain drive and a countershaft gearbox, and it was the superiority of this form of transmission for hilly going that had been demonstrated so convincingly.

Indeed, Indians had been chain-driven from the start in 1901, and it was all the more surprising that in that very year, 1911, they had broken with their own tradition to introduce a 600cc single with direct flat-belt drive to the rear wheel. A free-engine clutch was incorporated in the driving pulley, and a jockey wheel, carried on a bell-crank lever, pressed against the underside of the belt. By moving the lever, the rider could increase belt tension while on the move. This, said the makers, was for hill-climbing, when a much tighter belt was needed than for level going. However, the belt-drive Indian was but a temporary lapse, and before long chain drive was again universal

Indeed, Indians had been chain-driven from the start in 1901, and it was all the more surprising that in that very year, 1911, they had broken with their own tradition to introduce a 600cc single with direct flat-belt drive to the rear wheel. A free-engine clutch was incorporated in the driving pulley, and a jockey wheel, carried on a bell-crank lever, pressed against the underside of the belt. By moving the lever, the rider could increase belt tension while on the move. This, said the makers, was for hill-climbing, when a much tighter belt was needed than for level going. However, the belt-drive Indian was but a temporary lapse, and before long chain drive was again universal

Perhaps we can pin-point the start of the Indian saga as the coming together of two former racing cyclists, George Hendee and Oscar Hedstrom, at a cycle race meeting at Madison Square Garden’s, New York, in December of 1900. Each was already in a small way of business. Hendee was building bicycles in Springfield, Mass; Hedstrom, by trade a precision toolmaker, was in partnership with a man named Henshaw, building De Dion-powered tandems for motor-paced cycle racing.

Perhaps we can pin-point the start of the Indian saga as the coming together of two former racing cyclists, George Hendee and Oscar Hedstrom, at a cycle race meeting at Madison Square Garden’s, New York, in December of 1900. Each was already in a small way of business. Hendee was building bicycles in Springfield, Mass; Hedstrom, by trade a precision toolmaker, was in partnership with a man named Henshaw, building De Dion-powered tandems for motor-paced cycle racing.

But George Hendee had been mulling over the idea of making a simple, practical, everyday motor cycle for the average man, and he felt that Oscar Hedstrom was the right man to design it. They sealed the agreement, in pencil, on the back of an envelope, and Hedstrom went back to his workshop at Middletown, Connecticut. Throughout that winter he devoted his time to a prototype and, early in 1901, he took it to Springfield to show to Hendee.

Like the British Humber or P&M, it utilized the engine as an integral part of the frame, except that here it was substituted for the seat tube instead of the front down tube and, in consequence, sloped rearward slightly. That apart, the frame was of normal bicycle type, and the one and three-quarter horsepower Thor engine drove, by chain, to a sprocket on the pedal shaft. Fuel was carried in a small crescent-shaped tank on the rear mudguard. As was usual in 1901 the engine had an automatic (suction operated) inlet valve, but instead of a surface carburettor there was a spray-type carburettor designed and patented by Hedstrom himself.

George Hendee was delighted, so much so that he began to advertise the new machine immediately, even before he had settled the hire of the loft in which it was to be built. Choice of the name – Indian – took surprisingly little time; and, yes, it would have a painted red finish.

For all Hendee’s enthusiasm and optimism, putting the Indian into production was a protracted business, and only three machines were built before the close of 1901. Even so, remarkably, one of those had been shipped across to England for exhibition at the Stanley Show in London.

In the following year, production rose to 143 machines – and Hendee and Hedstrom, together with George Holden, had personally demonstrated the Indian’s capabilities by scoring a resounding one-two-three in the 280-mi1e New York to Boston endurance trial.

Wisely, Hendee and Hedstrom kept the design of the Indian unchanged for the first several years, and not until 1905 was there any major alteration. The engine was still a ‘bought out’ item produced for them by the Thor Manufacturing Company, but now the original cast-iron cylinder made way for a steel cylinder turned from a solid billet, and there was an engine-shaft shock absorber, combined with the sprocket, to give a sweeter transmission.

Also, the unsprung bicycle front fork was replaced by a sprung fork. The real novelty, however, was the adoption of the world’s first twistgrip control of the throttle and ignition. The same year saw the first Indian twin, though it must be said that it was experimental only, and didn’t go into production.

On 1906 singles, George Holden again hit the news when he and Louis Mueller established a new coast-to-coast record, but meantime the Hendee Manufacturing Company was preparing for its next major advance. This was nothing less than the building of its own engines, together with Hedstrom carburettors, and to that end much bigger premises had been erected on State Street, Springfield.

One of the first results of the move was the announcement, for 1907, of the first production Indian vee-twin. Angle between the cylinders was very narrow (only 42 degrees), and the rear cylinder, as in the single, served as the seat tube. One of the twins, nominally of four horsepower (600cc) travelled to Britain, where American rider T. K. Hastings rode it in the 1907 Thousand-mile Trial promoted by the Auto Cycle Club (fore-runner of the ACU).

An unusual 500cc overhead-valve single, with the valves operated by pull- rods instead of push-rods, appeared in 1908. One year later, Indian had abandoned the unique frame construction, and the programme included vee-twins of 5 ½ and 7 horsepower, with mechanical valve operation and an inlet-over-exhaust layout, housed in tubular loop frames. Another 1909 landmark was the coming of the Indian leaf-spring front fork, with the wheel carried on short trailing links.

Already, a London office had been established, with Billy Wells in charge (and Billy had persuaded Hendee that it was quite unnecessary to produce a special English-market version with belt instead of chain drive!). Now, with Wells as the driving force, Indians were going to launch a mass attack on the TT races, with a batch of the 5 ½ hp twins, specially reduced to 500cc. Billy Wells had included himself in the 1909 trio (the others were Guy Lee Evans and Gordon Fletcher) but had to withdraw from the actual race after hurting himse

lf during practice. Guy Evans went on to shock the crowd by holding the Indian in the lead for half the race, before finishing second behind Harry Collier’s Matchless.

Encouraged by this result, Indian tried again in 1910, the last meeting to be held on the old ‘short’ TT course based on St Johns, and this time there were four private entries (among them W. O. Bentley, later to make his name as a manufacturer of magnificent motor cars) in addition to the works team. But luck ran the other way, and there were only two survivors, both privateers; Jimmy Alexander was 14th, and Arthur Moorhouse 21st.

For the 1911 meeting Oscar Hedstrom himself came over to discover what TT racing was all about, bringing with him one Jake de Rosier, an American racer of tremendous repute in his own country. The official team this time was Franklin, Moorhouse and de Rosier (Godfrey, the eventual race winner, was a private entrant) and although de Rosier finished twelfth, he was disqualified by the organizers on technical grounds. So, too, was Matchless works man Charlie Collier, and the arguments in the press as to which was the better rider had to wait until later to be settled.

The ‘grudge match’, if it can be so termed, between Collier and de Rosier finally took place at Brooklands, as a best-of-three affair. Collier won the first leg, and de Rosier the second, so it all hung on the final leg. De Rosier won that, too – but, said Matchless fans, only because Collier had to stop while leading, to refit a loose plug lead!

Back home in Springfield, the Indian works were now on full song, and production rose sharply, to 20,000 machines in 1912, and 35,000 in 1913. But that was just chicken-feed, and for 1914 (by which time Indian had some 2000 dealers around the world) the total would rocket to 60,000.

Spearheading the 1914 range was the impressive 7hp two-speed Hendee Special, scoring another ‘world’s first’ for Indian by being equipped not only with electric lighting but with electric starting. Mounted in front of the engine and connected to the driving shaft by chain at 2 to l ratio, the generator served also as a motor, turning the engine at 500rpm.

Another 7hp twin had electric lighting but not the starting system. Contemporary advertisements claimed that there were, in all, ’38 betterments for 1914′, among them (on some models) a sophisticated swinging arm rear suspension, controlled by leaf springs, and precision Corbin speedometers driven from the rear hub.

For some little while, however, relations between Oscar Hedstrom and George Hendee had been becoming sour, and the Hendee Special was marketed against Oscar’s advice. Truth was, it was ahead of battery technology, and was destined to be dropped after only one season. It could be that this was the last straw, so far as

Hedstrom was concerned, for he now left the company, and did not return until after Hendee had retired 1916.

Riding one of the 7hp 1916 twins, electrically lit, but without starter, Erwin G. Baker set up a new coast-to-coast record of 11 days 12 hours 10 minutes, on a machine he had never even seen until three hours before the off. So rough were the tracks between towns that Baker – whose name was to live in motor cycling folklore as ‘Cannonball Baker’ – had to take to the railroad track at one stage, riding for 27 minutes on the railway sleepers.

To replace Hedstrom in the design office, Hendee brought in Charlie Gustafson, who had worked for Reading Standard. Charlie preferred a side-valve arrangement to the more familiar Indian inlet-over-exhaust, and this was evident in his 7hp: (990cc) Powerplus twins, revealed for 1916. Rather more of a surprise was a very trim little 225cc (64 x 70mm) two-stroke, with three-speed gearbox and all-chain drive.

In American racing Indian works riders had been campaigning an eight-valve ohv twin to good effect and now a production version was introduced. It was on one of these Indian eight-valver racing twins that Reuben Harveyson was later to make Brooklands history, by flying full-pelt over the top of the concrete banking. Yet another 1916 addition was a 4hp flat twin, but this never did gain the following of the vee-twins.

The American Army, thus far, had not used motor cycles for military purposes, but now came an order for fifteen Powerplus models, for service in Mexico in the expedition against rebel leader Villa. Others were supplied to the Italian Army, but on the entry of America into World War I, in 1917, the factory was turned over almost entirely to military work.

When civilian production was resumed in 1919, Indian had just about the strongest design team possible. Not only was Oscar Hedstrom back at his desk, but Charlie Gustafson had been joined by Charles B. Franklin, the Dubliner who had taken an Indian to second place in the 1911 Isle of Man Tourist Trophy event.

When civilian production was resumed in 1919, Indian had just about the strongest design team possible. Not only was Oscar Hedstrom back at his desk, but Charlie Gustafson had been joined by Charles B. Franklin, the Dubliner who had taken an Indian to second place in the 1911 Isle of Man Tourist Trophy event.

In the course of time, Franklin was to become vice-president of the company. Understandably, he persuaded Indian to have another crack at the TT in 1922 and 1923, and in the latter year he took personal charge of the racing team, when the top runner was Freddie Dixon; it was a near thing, but virtually certain victory slipped from Dixon’s grasp when a stretched valve caused him to lose three minutes.

Franklin’s most celebrated design was the 500cc vee-twin Scout, one of the best loved Indians that ever left Springfield, and a bike which was to become a favorite with fairground Wall of Death showmen. On a Scout, Paul Remaley in 1925 chopped the American coast-to-coast record to 5 days 18 hours for the 3700-mile journey, although this could be taken as indicative of improving road conditions. Remaley also broke the Canada to Mexico Three Flags record, setting up a new time of 46 hours 58 minutes.

An unexpected addition to the lower end of the range was Franklin’s 348cc side-valve single, the Indian Prince; more predictable was his new range leader, the 1234cc Big Chief. The little single, rather British in appearance, was intended to appeal to European tastes, but the company’s hope were blighted in 1925 when Britain clamped down on motor cycle imports by setting up a 33.3% tariff wall. Sales slumped so dramatically that Indian’s London office was forced to close down.

At the New York Show early in 1927 Indian created a sensation by announcing the acquisition of the handsome four-inline Ace and, moreover, the services of the Ace’s designer and chief engineer, Arthur Lemon. In the course of the next few years, the Ace was gradually assimilated into the Indian programme as the 1265cc Indian Four, but its ancestry was to remain evident in the general configuration of its engine until 1936.

That year, a very different (and to many eyes, much less attractive) Indian Four took the floor. Reversing the former arrangement, ithadoverhead exhaust valves and side inlet valves, the layout necessitating some clumsy exhaust- pipe plumbing. Customers gave it the raspberry and, realising that they had gone off-beam, Indian instituted a redesign immediately.

That year, a very different (and to many eyes, much less attractive) Indian Four took the floor. Reversing the former arrangement, ithadoverhead exhaust valves and side inlet valves, the layout necessitating some clumsy exhaust- pipe plumbing. Customers gave it the raspberry and, realising that they had gone off-beam, Indian instituted a redesign immediately.

This time they got things right, and the 1938 Indian Four emerged as a really beautiful piece of machinery, with the cylinders, and light-alloy cylinder heads, cast in pairs and topped by totally enclosed inlet-over-exhaust valve mechanism. The stylishly flared mudguards were like those fitted to the twins, which by this time embraced the 500cc Junior Scout, 750cc Sport Scout, and l200cc Chief 74.

Very deep mudguard valances, enclosing almost half the wheel area, were added for 1940. Plunger-type rear springing, too, had been adopted. But had enthusiasts only realised it, the Indian Four was nearing the end of the road. The last batch of fours – indeed, the last production fours in USA motor cycle history – left the factory early in 1942. By then World War II was raging in Europe and, following the treachery of Pearl Harbour, the Indian factory again switched to a wartime footing.

The machines were mainly 500cc side-valve twins for the Canadian and US Armies (but some were allocated to British Army use, also), although a very big departure from tradition was the production of a thousand Model 841 transverse vee-twins, with shaft final drive. Capacity was 750cc, and the cylinders were at a 90-degree angle; but at a colossal 540lb, the Model 841 was much too heavy to be successful.

Perhaps this is the right point at which to turn aside from the main stream of Indian history to examine a small tributary. This was the Torque Manufacturing Company, of Plainville, Connecticut, founded by the Stokvis brothers. It was the Torque concern’s intention to break into motor cycle production with a range of machines based on European practice, and to that end they engaged designer Briggs Weaver. He drew up a ‘modular’ series of engines – 220ce single, 440cc vertica1 twin, and 880cc in-line four – all employing the same cylinder, cylinder head, and overhead valve gear mechanism.

Layout of the 220cc single looked a little odd, with a separate exhaust camshaft at the front and inlet camshaft at the rear (it didn’t seem so odd on the 440cc twin, because this was what Triumph had been using) but the explanation was that in the in-line four, with four of the independent 220cc cylinders sitting on a common crankcase, the camshafts were at each side of the unit. Very much lighter than anything yet to emerge from an American factory, the Torque Manufacturing models featured telescopic front forks and plunger type rear suspension.

However, the Torque range was destined never to go into production under that name. Manufacturing rights were bought by Indian, and when the single and twin did appear (the four existed as a prototype only) they were the 1948 220cc Arrow and 440cc Scout. By the following year there were three versions of each 220cc Arrow, Silver Arrow and Gold Arrow, and 440cc Scout, Sport Scout and Super Scout – differing in the lavishness of their equipment.

Engine sizes were raised for 1950, the single now being 250cc and the twin (renamed Warrior) of 500cc. Indians were reported to be tooling-up for mass production, and with this in mind they had acquired the Springfield factory at one time used by Rolls- Royce of America.

Unhappily, the new machines proved to be a fatal investment. In appearance they compared reasonably with the British and European motor cycles now beginning to gain a foothold in the USA market, even if they did embody some very peculiar idiosyncrasies like widely splayed pushrods, each in its tube, and rockers that worked inside-out. There seemed no good reason, either, why the chain drive was on the right and the kick-starter and foot gear change on the left. But there were endless teething troubles, and production never even approached the target that had been set.

Another of Briggs Weaver’s designs was a gutless little unit-construction side valve 250cc named the Indian Brave, again with left-side kick-starter and gear change. This one was built, not at Springfield, but in Southport, England, by Brockhouse (the company which had manufactured the paratrooper’s folding Welbike scooter).

Another of Briggs Weaver’s designs was a gutless little unit-construction side valve 250cc named the Indian Brave, again with left-side kick-starter and gear change. This one was built, not at Springfield, but in Southport, England, by Brockhouse (the company which had manufactured the paratrooper’s folding Welbike scooter).

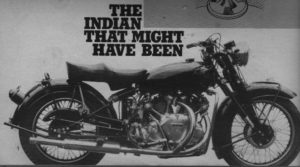

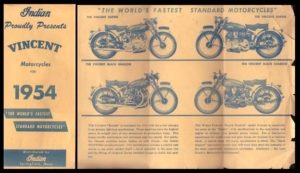

By, the early 1950s, it seemed as though Indian were threshing wildly in an attempt to keep afloat. Trying to salvage something from the impending calamity, they approached Britain’s Vincent-HRD company, who evolved for them two prototypes; the first was a most attractive model with 998cc Vincent engine in a typically Indian frame (unofficially, it was called the Vindian) but the other, less happy, married a vee-twin Indian engine with a Vincent frame (see History below)

Neither went into production, Indian preferring to sell, instead, the pure and unadulterated Vincent. Nor was it only the Vincent, because the Indian Sales Corporation was soon handling AJS, Excelsior, Matchless, Norton, and Royal Enfield, too. Their own production dwindled away to nil. By 1953 it had ceased entirely, and American dealers were selling a very mixed bag of so-called ‘Indians’, comprising Matchlesses and Royal Enfield Bullets with Indian transfers on the tanks. From the 1960s entrepreneur Floyd Clymer began using the Indian name, apparently without purchasing it from the last known legitimate trademark holder. He attached it to imported motorcycles, commissioned to Italian ex-pilot and engineer Leopoldo Tartarini, owner of Italjet Moto, to manufacture Minarelli-engined 50 cc minibikes under the Indian Papoose name. These were so successful that Clymer also commissioned Tartarini to build full-size Indian motorcycles based on the Italjet Grifon design, but fitted firstly with Royal Enfield Interceptor 750 cc parallel-twin engines,then with Velocette 500 cc single-cylinder engines.

After Clymer’s death in 1970 his widow sold the alleged Indian trademark to Los Angeles attorney Alan Newman, who continued to import minicycles made by ItalJet, and later manufactured in a wholly owned assembly plant located in Taipei (Taiwan). Several models with engine displacement between 50 cc and 175 cc were produced, mostly fitted with Italian two-stroke engines made either by Italjet or Franco Morini, but the fortunes of this venture didn’t last long. By 1975 sales were dwindling, and in January 1977 the company was declared bankrupt. The right to the brand name passed through a succession of owners and became a subject of competing claims in the 1980s, finally decided in December 1998 by a Federal bankruptcy court in Denver, Colorado.

The Indian Motorcycle Company of America was formed from the merger of nine companies, including IMCOA Licensing America Inc., which had been awarded the Indian trademark by the Federal District Court of Colorado, and California Motorcycle Company (CMC), an existing motorcycle fabricator. The new company began manufacturing motorcycles badged under the famous ‘Indian’ name in 1999 at the former CMC’s facilities in Gilroy, California. These motorcycles are often referred to as ‘Gilroy Indian’ motorcycles. The first model was a new design called the Chief. Scout and Spirit models were also manufactured starting in 2001. These bikes were initially made with off-the-shelf S&S engines, but used the all-new 100cubic inch Powerplus engine design from 2002 to 2003. The company went into bankruptcy again in late 2003, after a major investor backed out.

On July 20, 2006, the newly formed Indian Motorcycle Company, owned largely by Stellican Limited, a London-based private equity firm, announced its new home in Kings Mountain, North Carolina, where it has restarted the Indian motorcycle brand. The new Indian Chief motorcycles are produced in limited numbers, with the focus on outstanding quality, performance, and exclusivity. The limited production 2009 Indian Chief features a redesigned 105 cubic inch (1,720 cc) Powerplus V-Twin powertrain with electronic closed loop sequential port fuel injection. A new charging system provides increased capacity for the EFI.

Engine cylinders are Nikasil plated, eliminating the need for cast-iron liners. A new crankshaft eliminates “scissoring”The exhaust system is a new design with integrated 3-way catalytic converter and heated oxygen sensors. All body parts are e-coated and the frame and swing-arm are e-coated and powder coated for enhanced corrosion protection.

A six-speed transmission delivers power through the belt drive to 16 inch wheels out back. Stopping is achieved via Brembo 4-piston calipers, with 11.5 inch dual rotors at the front. Standard 5.5 US gallon tank helps extend cruising range. Seats are all-leather and built to exacting specifications.

Indian had announced its plan to have 50 dealerships within the US by the end of 2012, 25 of which have already been named. The flagship store, Indian Motorcycle Charlotte, located in Gastonia, North Carolina held its Grand Opening on October 4, 2008. International Dealerships in Canada, France , Japan, Korea, Switzerland, Russia, Monterrey,& Spain are operating with Australia-N. Zealand forecasted to open in 2011.

The Indian Dakota is a “Four” (4 cylinders in-line or “straight 4”) with shaft drive, 5 speeds, disc brakes and electric starting. This machine was designed in Sweden and later refined and put on sale in Britain as the Dakota by a former punk rock star and biker Alan Forbes This modern reincarnation of the fabled Indian Four it has a Volvo car crankshaft con rods & oil pump ( air cooled with performance enhancements) transmission is their own manufacture and the wheels, differential & shaft drive are BMW motorcycle. Volvo is Swedish and original Indian designer Oscar Hedstrom was from Sweden too. Production of the Dakota began 2000 by “production” is meant built-to-order rather than mass-produced. The Dakota 4 received a very favorable road test review in Classic Bike magazine a few years ago. It was available for sale in the USA (price about $30,000 which was low for a hand assembled machine). It is a genuine Indian since it is a product of Indian Motorcycle Ltd., based in the UK (specifically Edinburgh, Scotland, Britain), which is a different entity than the Indian Motorcycle Company based in King’s Mountain, North Carolina, USA (which was producing the V-twins described above). The US company bought the intellectual property rights from the Gilroy company’s bankruptcy trustee, but these rights do not apply to England. Click on highlighted link for more information www.indian-uk.com

The Indian Dakota is a “Four” (4 cylinders in-line or “straight 4”) with shaft drive, 5 speeds, disc brakes and electric starting. This machine was designed in Sweden and later refined and put on sale in Britain as the Dakota by a former punk rock star and biker Alan Forbes This modern reincarnation of the fabled Indian Four it has a Volvo car crankshaft con rods & oil pump ( air cooled with performance enhancements) transmission is their own manufacture and the wheels, differential & shaft drive are BMW motorcycle. Volvo is Swedish and original Indian designer Oscar Hedstrom was from Sweden too. Production of the Dakota began 2000 by “production” is meant built-to-order rather than mass-produced. The Dakota 4 received a very favorable road test review in Classic Bike magazine a few years ago. It was available for sale in the USA (price about $30,000 which was low for a hand assembled machine). It is a genuine Indian since it is a product of Indian Motorcycle Ltd., based in the UK (specifically Edinburgh, Scotland, Britain), which is a different entity than the Indian Motorcycle Company based in King’s Mountain, North Carolina, USA (which was producing the V-twins described above). The US company bought the intellectual property rights from the Gilroy company’s bankruptcy trustee, but these rights do not apply to England. Click on highlighted link for more information www.indian-uk.com

On April 19, 2011 Polaris (Victory Motorcycles) announces a takeover of Indian motorcycles with a new range within 12-18 months King’s Mountain plant will be closed down with production moved to Spirit Lake Iowa.Yet another page of Indian History continues stay tuned for future instalments!

The Indian’s That Might Have Been 1949- & How the Indian-Vincent was Resurrected

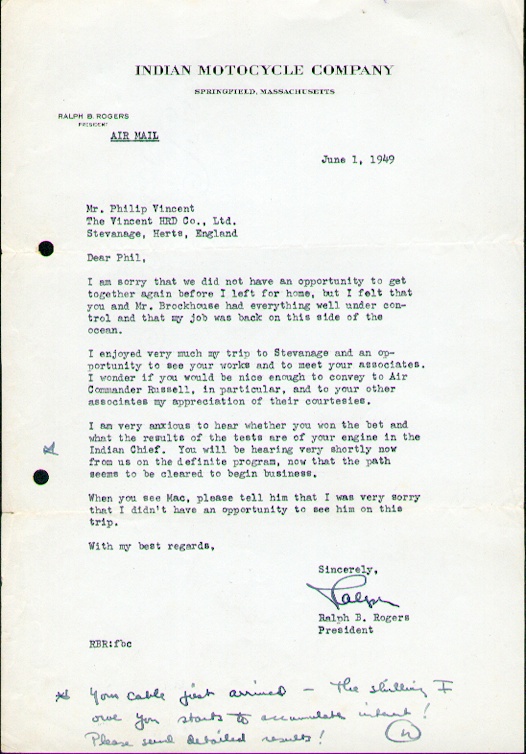

This story has two beginnings, one in 1949 and one in 1970. We shall start in 1949. I am fortunate to have a copy of the original letter from Ralph Rogers – (Indian Motocycle Co), to Philip Vincent – (Vincent and HRD motorcycles).

Ralph Rogers, manager of the Indian factory in Springfield was met by Philip Vincent in view to Vincent Motorcycles being distributed in the USA by Indian Motocycles. Apparently the two got along very well and in fact a joint proposition was put forward that possibly a Vincent could be made to suit more American tastes. This unbeknown to Vincent would help pull Indian out of a failing sales slump due to their lack of developing an O.H.V. engine to compete with Harley Davidson on more equal terms. For Vincent this would give access to a massive dealer network in which to sell his product including the supply of engine units. Unfortunately for Vincent, he never realised that Indian at this time Indian was close to being broke. Both men seemed happy with this agreement. It was decided two prototype be engineered, one in a standard Indian Chief frame, the Vindian, which much has been written about and the other one to be Vincent framed, the Indian-Vincent, with electrics, converted to left hand gearshift. Not many people realise this model even existed.

In 1949 a crate arrived at Stevenage from Springfield containing a complete Chief. Also included were the relevant bits to make the Indian-Vincent. Phil Irving (an Australian born engineneer, with Vincent) mentions in his autobiography that a machine was taken from the service department F10AB/1/3492 which in fact is a misprint as this was not made till late 1950. The machine used was F10AB/1/2492 and this is easy to prove from the original photos which thanks to todays technology can read the engine number quite clearly. As Phil mentions in his autobiography this eventually became the machine with a Blacknell sidecar attached that he returned to Australia within 1949. It was easy to track the Australian registered number (VIC 53148) and confirm the engine number & I now have a copy of Phil’s original registration certificate dated 07/03/50 (US – 03/07/1950).

The story on the Vindian has been well documented and the photo of Phil Irving astride this machine are common (see below). The Vindian after the photos were taken, the machine was stripped the engine returned to its Vincent frame. The Indian-Vincent assembled with parts Indian supplied from an Indian vertical twin was returned to standard Vincent Series C specs & the parts returned back to Springfield with the remnants of the Vindian . This included a Delco generator and regulator, park light for the front guard off a early version not the famous Indian head type, tailight assembly, base mount chrome G.E headlight, ignition/light switch, stop switch, horn and dipswitch buttons. The machine F10AB/1/2492 in fact was a Series C touring Rapide, so was already fitted with touring mudguards, crashbars (safety bars)wide handlebars and 3.50 x 19 front wheel and 4.00 x 18 rear wheel. As a 1949 model it had a plain motor. This was the transition period between H.R.D and Vincent trademarks and the motor was H.R.D. Ground off crankcases were being used in the mean time so it had a later diecast kick start cover and Vincent timing cover fitted. Surprisingly plain rocker caps were fitted because these were not available at the time. Another strange thing was a handful of engines were manually stamped Vincent, as in America the name and place of origin had to be cast or stamped on the crankcases as well as the manufacturer. An example of this is shown in MPH (Vincent Owners Club Magazine) (see below)

These handful of engines existed between numbers 2000 & 3000 which again proves Phil Irving’s printing error as 3492 was cast Vincent on the crankcase, as shown in the original pictures.

These handful of engines existed between numbers 2000 & 3000 which again proves Phil Irving’s printing error as 3492 was cast Vincent on the crankcase, as shown in the original pictures.

The proposed orders from Indian were 50 Vindians and 20 Indian-Vincents a week. This was a fairly good deal for Vincent but unfortunately never came to fruition. Vincent had in fact bought and ordered the material to produce these machines but never recieved an order from the cash strapped Indian corporation. This put Vincent in a bad position, so bad they were placed in the hands orf the receiver, E.C. Baillie. Meanwhile the photos were taken of the Indian-Vincent. It was close to standard specs but it was not road tested as thoroughly as the Vindian, after the orders were cancelled. Philip Vincent gave orders that the Chief be returned to the Indian Factory complete with it’s original Indian engine and the extra pieces supplied for the Indian-Vincent.

There is speculation that Indian did in fact fit a Vincent engine back in this frame, as at this time Indian started distributing Vincents in America and therefore would have been capable of doing this. In fact this machine still exists and it is now part of the Du Pont family museum, previous owners of the Indian Motocycle Company.Phil Irving left England in October 1949 and brought with him the Indian-Vincent which had been returned to original specs. Phil eventually traded the outfit for a Vauxhall Wyvern car in 1953 and lost contact with the motorcycle. Ironically Vincent was distributed through Indian Sales Corporation in America with a small handfull of agents specializing in servicing & repairs such as Gene Aucott, average Indian franchises had difficulty in repairing complicated & sophisticated European designs unless the were previously trained in such methods therefore sales were never as good as initially expected.

1970 and On.

In 1970, Philip Vincent wrote an article for Motorcycle Sport Quarterly, an American Magazine, titled “The Indian That Might Have Been”. I bought this magazine as I was interested in Vincents and like most people were repulsed by the photo of the Vindian. I wondered why the Indian-Vincent had never been produced. Little of the technical specs were available but detailed shots of both sides of the two machines were included.

I bought a Vincent motorcycle in pieces that had been raced in it’s earlier years. It was basically all there and I remember thinking how much trouble someone must have gone to make up a die to stamp VINCENT on the crankcases as it was an excellent job. I was also amazed that the pictures in Motorcycle Sport Quarterly of the Indian-Vincent’s crankcase were stamped in the same manner. Months later in an article in M.P.H., the Vincent Owners Club magazine, I discovered that it was in fact a factory modification used on engines numbered between 2000-3000.I contacted Robin Vincent-Day, Philip Vincent’s son-in-law as he was advertising a Indian-Vincent tank decal and I asked him to send a photo. I also asked if he could send me any information about this little known Vincent. Robin was very helpful and in fact sent me not only the information but also four previously unpublished photos of the left hand and front shots of the Indian-Vincent. At this time, I casually mentioned the way the Vincent crankcase was stamped in the photos was the same as the machine I had. Could it be possibly be the same one? I told him of the numbers on my engine and he then sent me blow-ups of the crankcase numbers in the photos. We were utterly amazed when they turned out to be the same number. I remember running out to the garage as the enlarged photo came up on my computer screen checking and rechecking that the numbers were in fact the same. I am indebted to Robin and Deidre Vincent-Day for the help in confirming the history of my bike.This news put me into a dilemma as to how to restore the bike. I had two options. I could build, a Indian-Vincent or restore it to Phil Irving’s original outfit of a touring Rapide with Blacknell sidecar.

I decided Phil’s outfit would look just like any other Vincent with a Blacknell sidecar attached so this left the only option, to restore this piece of Indian history.When I was about half way through the restoration, the gear change conversion had proved to be tricky. The brake swap was achieved by using a Vincent Comet brake cable and the generator conversion by jack-shaft is strange. The ignition/light switch mounted in the centre of the handlebars is very weird considering it is a Lucas magneto, the taillight is a real bolt-on after thought and I can see why those lugs were cast but never used on the Girdraulic forks for the headlight, this is the lug used on the Indian application. I had to find a Blacksmith to fabricate the mount for the headlight. The horn mounts on the engine where the coil fits on a Series D. Pictures show the battery as a block of wood as apparently Indian never sent one of their batteries to Vincent. I have fitted 12v battery with the modified battery carrier for 21st century use.

I decided Phil’s outfit would look just like any other Vincent with a Blacknell sidecar attached so this left the only option, to restore this piece of Indian history.When I was about half way through the restoration, the gear change conversion had proved to be tricky. The brake swap was achieved by using a Vincent Comet brake cable and the generator conversion by jack-shaft is strange. The ignition/light switch mounted in the centre of the handlebars is very weird considering it is a Lucas magneto, the taillight is a real bolt-on after thought and I can see why those lugs were cast but never used on the Girdraulic forks for the headlight, this is the lug used on the Indian application. I had to find a Blacksmith to fabricate the mount for the headlight. The horn mounts on the engine where the coil fits on a Series D. Pictures show the battery as a block of wood as apparently Indian never sent one of their batteries to Vincent. I have fitted 12v battery with the modified battery carrier for 21st century use.

Now you may ask would it have saved Indian. Well it would have had to have more development on the gear-change. The bike never had a formal road test like the Vindian because it did not change gears very well as the factory engineered it, the trouble to make it a R/hand rear brake to suit Indian Owners was not worth all the effort. The gear-change lever had about 5″ of lever movement throughout it’s arc, now I have halved this with rose joints instead of clevi’s that Vincent originally used. The original lash-up the factory used for the generator in the factory photos show the generator belt loose on the pulleys so I fitted a modern multi groove belt which works very well. The electrical system is now 12 volt instead of 6 volt. As previously mentioned the factory fitted a block of wood which was neither voltage.I think Indian did the right thing in the end by just importing standard Vincents. The Indian-Vincent would have been still unfamiliar to the traditional Chief/Scout owner.Possibly for Vincent it was easier to sell complete machines which would have been cheaper to produce than a hybrid of both manufacturers, but Vincent would have benefited more than Indian overall.”

Phil Pilgrim